CORNISHMEN FOR THE WITWATERSRAND MINES

Jeff Woolgar

The Postcard

The history of the Cornish miners who travelled over 6,000 miles to find work in southern Africa is one of those historical events which is perhaps under recorded outside Cornwall. When researching Chinese labourers working the Witwatersrand mines, I was surprised to find only a few of those picture postcards of Chinese Indentured Labourers were addressed to Cornwall, I expected many more; I think it ran at four percent of postally used cards. Alas, none of these had messages. Perhaps they preferred to send other postcards with non-industrial and non-Chinese mine pictures.

The picture postcard above is a photograph with caption reversed out in white, 'Cornishmen Leaving Redruth Ry Station. / for the African Gold fields. 469' and at lower right is an imprint 'All Series.'

According to G.B. Dickason, the beginnings of the exploitation of the South Africa’s mineral wealth occurred at the time when the tin mines in Cornwall were being depleted. Moreover, the discoveries of large deposits of copper from around the world weaken the returns of the Cornwall mining industry. For many it therefore became necessary to find new employment, it was fortunate that there were prospects in southern Africa for those miners willing to undertake the long journey.

By 1895 there were around 8,700 Cornish men working on the Witwatersrand mines, of which about half were working below ground. However, not all the Cornish men came direct from Cornwall, as there were many independent miners working at other locations around the world, who made their way to southern Africa. The advantage with the Witwatersrand and the city of Johannesburg that sprang up nearby was the discovery of other minerals. Before the South African War (1899-1902) the population of the city was about 100,000; fifty years later it was 600,000. Deep level mining could not have been possible without the close proximity of coal from Boksburg, Heidelberg and Springs, the vast improvements in transport (Railways), and affordable African black labour. As with black African labour there was competition between agents to recruit Cornish men. Those who had been trained at the ‘Camborne School of Mines’ appear to have done well in southern Africa. As the men left Cornwall to earn high wages, some local mines became short of staff. Dawe, references to the Levant Mine on the coast of western Cornwall, near St Just.

Dawe also records the Witwatersrand 'wages earned by miners working a six day week' [5½?], who were paid around £5 and could send as much as £15 a month home to their families in Cornwall; which significantly helped the economy back home.

Nevertheless, Johannesburg, part of the so called competitive area was an expensive place to live; both private health matters and lodgings were high. Therefore, salaries needed to be ‘considerably higher’ than in other parts of southern Africa. There were many temptations to spend money, luxurious shops as almost everything had to be imported, and then there were the races and other forms of gambling. The population of Johannesburg (aged over 15 and less than 40 years) in 1895 was 73,321 of which only 12,172 were women. Of these 10.8% were said to be prostitutes! There was a traffic of such girls from around the world which continued until 1902 when it was prohibited. The red-light areas (brothels) were said to be in Loveday Street, Jeppe Street, Fraser Street, Snal Street and Von Wiellish Street. Then there were many bars, which had their own girls. As men outnumbered women, men often danced with other men, '... before falling over then tipsy'.

Excess drinking was a way of life for many miners. They drank spirts not beer. Some of the smaller mines purchased wholesale spirts at a low cost and sold it to the miners to make a profit. Nesbitt writing about the years from 1912 recorded that they earned good money, and squandered it; ‘They could not see one another dying …’. Mine owners supplied special masks, and took other precautions to combat the dust underground to see if it could be caught at source, special vapours were used and so on; all to no effect. ‘Men worked out their eight years, or less or a little more'. There were those victims caught by unexpected falls of rock, premature explosions of blasting charges and the like. When a miners' health was impaired by asthma or pneumonia they became destitute. Those affected by phthisis often could not return home, as they needed to remain at the high altitude and dry climate of the Witwatersrand.

The picture postcard is captioned 'Johannesburg The Balcony Tea Rooms' in red above was published by Sallo Epstein & Co. It entered the post on the 15th January 1906. Addressed to Fore Street, [near] Camborne, Cornwall. The Johannesburg seven-storey ‘Cuthbert Shoe Store’ was situated on the corner of Pritchard and Eloff Streets. Built in 1904 and designed by Bannister and Scott, the 'Corner lounge Tearoom’, where the Mackay sisters played, became a fashionable place. The message on both sides of the card, "What do you think of this building. There is some fine Buildings out here / I seen Jack yesterday". It is perhaps peculiar that the writer records that he saw "Jack" yesterday. Given that most men from Cornwall were thought of as 'Cousin Jack'.

Most of the picture postcards posted from the Transvaal Colony to Cornwell have no message, while the few that do are brief. One that has a picture of 'Jeppe Esq's House, Belgravia', he stands near a motorcar, was posted to High Cross Street, St Austell, Cornwall. It simply says “Am awfully busy – good wishes”. In other words; ‘sorry no letter this week’!

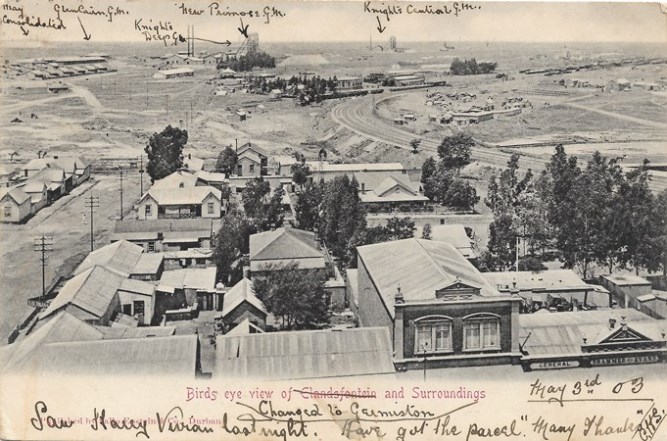

The picture postcard here has an undivided back printed in black, it was posted from Germiston on the 4th of May 1903 to the same address in St Austell as the Jeppe motorcar card mentioned above. It is captioned in red, 'Birds eye view of Elandsfontein and Surroundings'. 'Elandsfontein' has been crossed out by the sender of the card who has added "Changed to Germiston". They added the date and penned the card, "Saw Harry Vivian last night. Have got the parcel Many Thanks GHS."

On many view cards writers often record the names of buildings, mines etc. In the picture here 'GHS' has pointed out the Gold mines, some of which are only just visible.

From left to right:

May Consolidated (Producing mine for A. Goerz & Co.)

Glencairn Gold Mine (Producing mine for Consolidated Investment Co.)

Knights Deep (Non-producing mine for Consolidated Investment Co.)

New Primrose Gold Mine (Producing mine for Consolidated Investment Co.)

Knights Central Gold Mine (S. Neumann & Co.)

L. M. Nesbitt records in his book 'Gold Fever':

Presently we could smell the smoke of the lighted fuses, as it drifted towards us along the gallery; and then came the detonation of the exploding charges, followed after a few minutes by whiffs of dynamite smoke. The air gradually became thick and nauseating, tasting acrid and sweetish. The explosions had flung up great clouds of dust in the workings. … in the shaft the drip-drip-drip of water was heard continually, and from time to time quantity of stones fell, some of them striking the platform and causing the men on it to draw back.’

The healthiest men, those who had inherited from their forbears no trace of tuberculosis, naturally held out the longest, but no one was immune from the gradual accumulation of quartz dust in the lungs, and he was a healthy strong man indeed who lasted longer than eight years. The fine grit, so light that the movement going on in the air was quite sufficient to hold much of it floating in suspension for an indefinite time, consisted of minute particles with points far finer than that of any needle and edges infinitely sharper than that of a knife. …

Thus, some miners returning home to Cornwall because of the South African War from 1899 were found to have phthisis. Six hundred were reported to have died and the effect of that disease was to affect the lives of many who fell into structural poverty.

Not all of the men who went to southern Africa were miners; the picture postcard above was posted to London and entered the post at Middelburg on 15th July 1907. The handwriting is understood to be that of Alfred John Friend, known as ‘Jack Friend’ who was the Postmaster at Braamfontein in the South African Republic on the 1st September 1900. By which time he had been employed for almost eleven years in the service of the South African Republic. Following the South African War he was employed by the Transvaal Civil Service in various positions and localities in the Post and Telegraph Department, and by 1910 he was the Postmaster at Klerksdorp - see Woolgar (2021). ‘Jack Friend’ was still corresponding to Cornwall once the Union of South Africa was constituted; for on the 1st January 1912 he was writing from Klerksdorp to a W. Spurrell of Plymouth. Therefore, like so many of his post office contemporises he had worked for the South African Republic, Transvaal Colony and the Union of South Africa, without moving very far in twenty years.

Conclusion

Historians need to be careful not to impose the past by their own standards. The wealth and posterity of those who benefited from relocation in the mining or in any industry often do not appear in published government papers. Conversely, those who were indigent and could not maintain themselves and their families may be the subject of endless Commissions appointed by His Excellency the Lieutenant Governor of the Transvaal. Therefore, even going back to original source material the historian needs to be wary and examine as many documents, official gazettes, journals and memorabilia as possible. For those that did well by sending, say, £12 home each month to feed and house a family of five, may have been preferable to his Cornwall wage of, say £8 to feed and house a family of six.

Acknowledgments

I thank Rosemary Hawking, for information regarding a ‘South African, Cornish connection cards and postage exhibition’, which took place in Cornwall during 2012. It is pleasing to recorded it was viewed by circa 600 visitors in just six hours. Thanks also to Gail Tompkins for reading and correcting the second draft, and to the late Joan Matthews who provided all the picture postcards illustrated here.

References

Board, Christopher, (1967), ‘Southern Africa’ in, Hodder, B.W., and Harris, D.R., Africa in Transition, Methuen & Co. Ltd., London, pp.340-370. Cripps, Elizabeth Ann, (2012), Provisioning Johannesburg, 1886-1906, submitted, Master of Arts in History at the University of South Africa, p.79.Dawe, Richard D., (1998), Cornish Pioneers in South Africa, St. Austell, Cornwall, pp.117-131, 123, 148, 149, 196, 225-241, 236, 243, 244, 250, 257-258.Dickason, Graham B., (1978), Cornish immigrants to South Africa, The Cousin Jack's contribution to the development of mining and commerce 1820-1900, A.A. Balkema, Cape Town, pp.passim.Levy, Norman, (1982), The foundations of the South African cheap labour system London, pp.251-252.Nesbitt, Lewis Mariano, (1936), Gold Fever, Jonathan Cape, London, pp.30-31, 166.The Barnett Collection, a pictorial record of early Johannesburg Vol.2, (1966), ‘The Star’, Johannesburg, (Pages not numbered).The Transvaal Philatelist, Vol.32, No.2 May 1997, (122), p.xvi.Woolgar, J., (2021), TRANSVAAL Postal Department staff before and after the South African War, Gravesend, pp.18, 60.

- - 'Blasting Certificates' (Published here during LATE December 2025) - -- - Messages from Transvaal Gold Mines - -- - Back to Home page. - -

Copyright © J Woolgar 2025

- - o - -